The Osprey Among Us

You see them diving into the Intracoastal Waterway, hear their calls along the beach as they hunt, and watch their babies grow from the bridges. Osprey have made themselves at home here, take some time to get to know this unique bird of prey. By Jennifer Tuohy. Photos by Rob Byko.

As you walk along the beach, before the heat of the day descends, listen for a distinctive, high-pitched whistling. e loud “chirp, chirp, chirp” means you are about to see one of nature’s most spectacular ‑ Sherman in action. Look up and spot a flying body larger than a seagull and far more focused, hovering high above the breaking waves. A white underside, speckled with dark brown, piercing yellow eyes, a giant wing span and a distinctive raptor beak reveal this bird to be no mere gull, but a sea hawk; a lean, mean, ‑ shy killing machine — the osprey.

Watch for a minute more and you may see a terrifying dive, an abrupt underwater struggle and the osprey rising triumphantly from the sea with a fish between his claws. e Pandion haliaetu sometimes achieves success rates as high as 70 percent on its fishing trips. Several studies have shown the osprey catch fish at least one in every four dives. Compare that to your cast rate... jealous yet?

While the osprey may be a better fisherman than any of us, he does have to contend with something we don’t worry about while trawling or fishing on a dock — eagles. Smart creatures that they are, eagles have figured out osprey are better at catching fish; so, they rob them. Aerial battles between a dogged osprey and a determined eagle are some of the most epic in the avian world, and the ultimate treat for ornithologists and wildlife photographers alike. It’s called kleptoparasites, and eagles are pretty good at it. is penchant for thievery is one of the reasons Benjamin Franklin didn’t want the eagle to be our nation’s symbol.

“He is a bird of bad moral character; he does not get his living honestly,” argued the founding father. “You may have seen him perched in some dead tree where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the labor of the fishing hawk and, when that diligent bird has at length taken a fish and is bearing it to his nest for his young ones, the bald eagle pursues him and takes the ‑ sh. With all this injustice, he is never in good case.”

BUILT TO FISH

“Osprey could not be engineered more perfectly,” Jim Elliott, founder of e Center for the Birds of Prey in Awendaw, says. Unlike the more cumbersome eagle, the osprey has several adaptations that make it reign supreme at the fishing game, including reversible outer toes, sharp spicules on the underside of the toes that feel like sandpaper and help grip slippery fish, closable nostrils to keep water out during dives, and dense oily plumage to prevent its feathers from getting waterlogged when submerged. e osprey doesn’t swim however, instead it flaps the tips of its wings to raise its elegantly and impressively out of the water, wriggling fish in tow.

“They’re really unique birds, their diet is almost exclusively fish,” Elliott says. “ ese birds are very much specialists, they’ve been evolving to do what they do for a very long time. Some estimates put the species at three million years old.” So unique among raptors is the osprey that it has its own category — Pandionidae — of which it is the only member.

ISLAND LOVERS

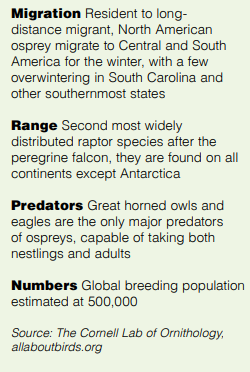

The Lowcountry is one of the few spots in North America that boasts a year-round population of osprey (see map). A highly migratory species, the northern dwellers come to our shores in the winter, taking the place of our nesting pairs who go further south. Come February 14 however, the “locals” begin to return to reclaim their nests and meet up with their partner (ospreys’ mate for life) to begin the process of producing the next generation.

Occasionally, upon their return, they may, and an orange cone placed rudely on top of their nest, or a stray great horned owl chick in residence. (‑ e owls, like the eagles, often take advantage of the osprey’s hard work. Mary Pringle, an Isle of Palms resident and volunteer at ‑ e Center for Birds of Prey, once found an owl chick that had been bumped out of the nest by an osprey).

Despite these setbacks, osprey is thriving in South Carolina and across their entire range, which is one of the largest of any bird of prey. Since rebounding from the DDT/pesticide catastrophe that decimated raptor populations, the bird has become very comfortable living with humans, often taking to manmade structures such as electricity poles, stadium lighting, chimneys and navigation aids on the Intracoastal Waterway to build their nests.

Unfortunately, the nest doesn’t always mesh with the structure’s intended purpose, and in some cases can be lethal to the bird and its o - spring, so deterrents, such as orange cones, are placed in them by electrical companies or homeowners before the birds return.

“Nest site deity — returning to the same site year after year — is as strong in ospreys as anything I’ve ever seen,” Elliott says. “they’re very determined. Once they choose one, that is their spot, no matter what humans might do to discourage them.”

To combat this stubbornness, erecting a special osprey platform can encourage a move. ‑ e islands boast at least four of these; at the end of Ben Sawyer Bridge, o Station 19, at the Sullivan’s Island Fire Department boat landing, and one of the IOP Connector.

Ospreys like platform nests for anatomical reasons. they hover and drop onto a perch, coming in from above, rather than swooping in from the side. Which is why in an entirely natural setting they choose dead trees to nest in, less foliage to get in the way. Basically, utility poles are just asking for osprey to nest on them.

A RELUCTANT STAR

This a section for man-made objects has thrust the osprey into the limelight, unintentionally making them one of the more obvious raptors in a populated area. ‑ e Lowcountry had about 300 nesting pairs back in 1986, today there are over 1,000, according to Elliott.

“They’ve done well,” he says. “DDT really knocked them back, and they are still listed as threatened in some states, but I’d say we’re near capacity in the Lowcountry. They are tolerant of us and of one another — which is unusual. Osprey will nest close enough that they are almost a colony. They’re not particularly social, but neither are they competitive.” Unlike the eagle.

Next time you see an osprey on our islands, whether studiously building his enormous stick nest, or soaring above the water in search of a tasty red fish, take a moment to appreciate this ancient creature. He is truly an example of how strategic evolution and a hard-wired single-mindedness has made the osprey one of the most successful raptors living among us.