The Cultured Affairs Of Island Oyster Roasts

By Jessie Hazard. Photos by Steve Rosamilia.

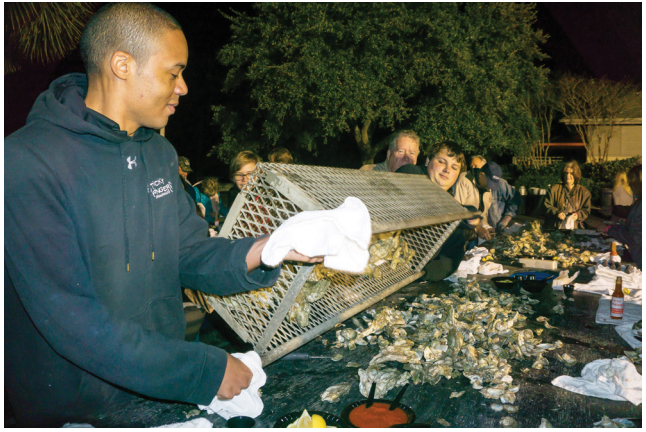

“Comin’ through, make way, coming’ through!” Jimmy Carroll and Marty Bettelli of the Isle of Palms Exchange Club bellow and grunt, each hoisting up an end of a colossal metal basket heaped with steaming, fragrant oysters. Guests at the Exchange’s 18th Annual Oyster Roast jostle each other a bit, shadowboxing an effort to clear the way for the basket bearers, but they make no heart-filled attempts. Always, all eyes stay on the basket—patience is not a virtue here—and heads comically bob along with its every swerve, the way a litter of kittens watch a laser-pointer. Finally, the sea of people parts just enough to allow a tumble of oysters to clatter onto one of the long wooden tables. As suddenly as they’d parted, the waves of people converge, and though lively conversation still skitters across the waterfront deck, the clacking of shells and scraping of knives take equal measure. These people are here with a supreme purpose: to roast.

The Charleston area is home to a veritable cornucopia of seafood, much of it interchangeably used as the centerpiece for many a local get together. There are fish fries, shrimp boils, crab pots. Ask most any Sullivan’s Island or IOP native, however, and they’ll tell you they prefer an oyster roast. Tough the others offer inarguably delicious fare; oyster roasts foster a sense of community less present elsewhere. There’s something about slumping over a long, splintered table with your fellow man, muddy to your elbows as you battle bivalves, that just brings people together.

Al and Linda Tucker have lived on Isle of Palms for over 40 years, and they return to the Exchange Club roast every year. “The most unique thing about oyster roasts,” says Linda, “is the atmosphere they create. Something about the oysters make things more conversational, more community-oriented. They’re a relatively unusual food to eat—luscious, salty, fun to pick—but not something you have in your kitchen every day. It’s that strangeness that makes them seem so special, and that’s what gives everyone something to gather around.”

And it’s true. Some of the newcomers cast furtive glances, self-consciously trying to figure out the best shucking method. Within minutes, the mavens are demonstrating, sliding the oyster knife into the sweet spot where the shells meet and giving a twist, then passing the meaty half shell back to the amateur. People across ages and circumstance, strangers only moments before, are building kinetic bridges over the valleys of oyster shells—they laugh, trade tools, tell stories, crack jokes.

The camaraderie runs deep not only with attendees, but with organizers as well. Carroll and Bettelli, along with Chip Stehmeyer and John Bushong, head a crew of roast veterans that are the lifeblood of the Exchange club event. The pack stands around giant steamers, chortling and gossiping, waiting for the right moment to pull fresh bushels of single select oysters from the water. They’ve got this down to a science, no easy feat: a minute too long and the oysters become rubber, pull them too soon and you’re looking at a hot, soupy mess. The troop gets it right every time. Diners are treated to supple oysters that still retain some of their intoxicating liquor. “It’s the perfect consistency for everyone,” Bushong’s wife Anne says. “Whether you’re new at this or you’re seasoned, you’re going to be happy. You get all of the good favor from the oyster without the raw and runny aesthetic that makes some people squeamish.”

A good oyster, like most good things, is a product of condition and time. This year, South Carolina has seen a particularly fine batch of local oysters, and some of the nation’s recent weather idiosyncrasies have yielded fine specimens from other regions. The roasts take full advantage of these resources, both local and afar. But ask anyone here—truly, anyone—what makes a good roast, and the oysters take back-burner. The first answer is, unfailingly, “the people.”

It’s this zealous kind of fellowship that also makes oyster roasts a profitable business. This year’s Exchange Club roast raised over $13,000 in scholarship money for community schools. Over at the Sullivan’s Island Fire and Rescue roast, Chief Anthony Stith annually leads a fearless crew that, though they turn a more modest pro ft, requires a whopping $18,000 on the front end to put up the event. These food-oriented fund-raisers have a deep-seated tradition with the SIFD. It all started in 1949, when a fire fighter’s sister-in-law needed surgery. A group of volunteers put on a fish fry and raised $10,000—no small sum then or now. When they decided to try a hand at oyster roasting two decades ago, the Fire Department saw another philanthropic avenue light up, and has been hosting them ever since—with an increasingly loyal following. “The $5 fish fry is really just more of a tradition now, so we keep doing it,” Stith says, who relies on the money from these events to fund nearly a half of his rescue division’s budget. “The oyster roasts are what people seem really attracted to, and they’re where we make most of our pro ft.” Tree years ago, the East Cooper Meals on Wheels program smartly jumped on the oyster roast bandwagon and are now seeing a return on that investment.

Isle of Palms restaurants Morgan Creek Grill and The Dinghy feature seasonal weekly oyster roasts as well—though their motives are decidedly more business-minded. “I don’t even make money on the oyster sales,” Bret Jones, owner and operator of the Dinghy, says. “But it’s a sure way of getting people to come in, talk to each other, buy a few beers, and most importantly, come back.”

It seems quaint to say that these roasts are capable of a level of moral consciousness you might find in a Girl Scout, but it’s true—particularly for those roasts that fundraise. Shells are recycled to help rebuild the oyster beds. Retailers like Simmons Seafood in Mount Pleasant consistently supply thousands of pounds of the signature shell fish, and they don’t mark it up for their trouble. Volunteers come early to set things up and stay late to tidy them away. The do-gooderism is ratcheted so high that it’s contagious, even for the most hard-shelled attendees. Patrons trickle from the fests in high spirits, buoyed not only by shell fish and beer, but by each other.

While the oyster meat may be the thing patrons take in at the roast, it’s a pearl of togetherness that they hold onto long after the shells are cast away.