Gazing At Great Blues

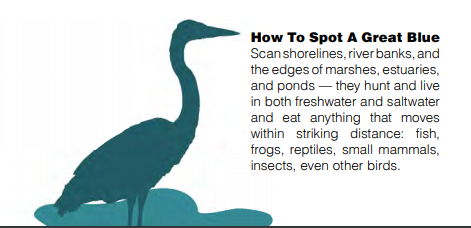

A closer look at this stoic shoreline fisher who graces our streams, marshes and creeks. Meet the Great Blue Heron. By Jennifer Tuohy Photos by Rob Byko

You may have spotted the Great Blue Heron that hangs out at Breach Inlet between Sullivan’s and Isle of Palms. He’s been a regular there for the last few years. “He walks up to fishermen and steals their bait,” says Emily Davis of ‑ e Center for Birds of Prey Avian Medical Clinic. While this bird is something of an anomaly (and one not to be encouraged), his ingenuity highlights what Great Blues are best at: adaptability.

“They are so adaptable, you can find them just about anywhere,” says Davis. Consequently, they are much-loved by locals and visitors alike. “People have this relationship with these birds,” says Davis. “When you’re out fishing, you’re almost fishing with them. But it’s under their terms.”

While their crude, croaky call may sound like a toad in its death throes, their statue-like beauty is nothing short of majestic. ‑ e Great Blue Heron is one of the Lowcountry’s true gems; common, yet eye-catching; slow moving, yet mighty. ‑ ese giant creatures stalk the waterways surrounding our islands, holding their giant 3- to 5-foot high frames motionless, ready-to-strike for hours on end as they scour the creeks and ponds for tasty tidbits to spear or gulp.

Big Blue

The largest of the North American herons, the Great Blue thrives in many habitats from the American South to Alaska. It was once close to extinction, thanks to a fashion for wearing its silky blue-grey plumage in hats, but today it is doing well.

In the air, the Great Blue is a majestic sight. With a wingspan of up to 6-anda-half feet, they can cruise as fast as 30 miles an hour, aided by their featherlight bones (they weigh less than 6 pounds, still heavy for a bird). They’re easy to differentiate from cranes while airborne, courtesy of their elongated S-shaped neck curled neatly into their body, long legs dangling awkwardly below.

Watching the Great Blue during its solitary hunt, you might assume they are lonesome souls, and you’d be correct. Until it comes to family time. Then they gather together in their hundreds in large nesting colonies are known as “heronries.” While tall trees are the nesting preference, you’ll sometimes find them in low shrubs. “They’ll choose islands where there are alligators, to protect them,” says Davis. While the chicks are very vulnerable to predators, the adult heron has few natural enemies, often living to 15 years of age. They’ve been known to mortally wound birds of prey but can fall victim to bobcats and coyotes.

Heron Helpers

The biggest threat to this beautiful creature is us. At the Awendaw-based Avian Medical Clinic, they typically see 80 to 100 injured Great Blues a year. “About half of them are entanglement issues, from fishing line and the like,” says Davis. “‑ e other half are leg issues.” Davis herself had a close call with a Great Blue who flew over the top of her car. “I had my sunroof open, and his legs hit my head through the sunroof — I could feel him go through my hair,” she says. Thankfully he was ne, but many aren’t. “It becomes a pretty fatal situation; their legs are so slender, and you can’t really x those bones.”

While they often appear stoic and calm, these gentle giants will fiercely defend their feeding territories from any avian intruders, courtesy of a dramatic display that includes stalking with their head thrown back, wings outstretched and bill pointing skyward.

Bear that in mind next time you’re lucky enough to be standing near one while fishing or bird-watching, and don’t get too close!