Creating A Community: How JC Long Built Isle Of Palms

In 1944 J.C. Long had a vision, a bustling barrier island town, home to middle-class houses and a middle-class community. Today, those mid-century houses may be dwarfed by multi-million-dollar homes, but they are still the heart of a vibrant community.

By Susan Hill Smith. Photos by Mic Smith.

An aerial shot of Isle of Palms, 1949. (Photo courtesy The Beach Company)

My husband and I wound up living on Isle of Palms by accident. We moved to the Charleston area in the fall of 1994, in our 20s, and needed a rental with a fenced-in yard for our two dogs.

J.C. Long’s two daughters help with a groundbreaking as mid-century development of Isle of Palms gets off the ground. (Photo courtesy The Beach Company)

To our happy surprise, Isle of Palms had one of the few available in our modest price range. Earlier that year, Mic and I had vacationed with extended family on the island in a new, three story oceanfront houses. Gigantic homes and Front Beach—that’s all we knew of Isle of Palms— until we turned onto 21st Avenue and saw the 815-square-foot house that would be our home for six months.

Built on a concrete slab foundation, the one-story cottage dated to 1962, though it seemed a decade or two older. With a few steps, we walked through the living/dining room and the galley kitchen. I sized up the smaller of the two bedrooms, uncertain whether it would ft a double bed. Mic considered the distance to the beach access path: two blocks. Given that, we agreed to squeeze in and stretch our budget for the $700-a-month rent.

J.C. Long’s companies constructed most of the interior Isle of Palms homes built from 1945 to the early 1970s. More than a few of those homes have disappeared over the years, but there are many left that you can still identify. (Photo courtesy The Beach Company)

I’m not sure who told us we were living in a “J.C. Long house,” a moniker for the man who made Isle of Palms into a both a working-class community and post-World-War II beach destination. But as we explored the island, we came across more two-bedroom cottages like ours and felt connected to them. Even after we moved into a larger, split-level home on 23rd Avenue, I would wonder about the history of the small houses, and their future.

Two decades later, I took time to fully investigate and learn about J.C. Long’s substantial and complicated impact on Isle of Palms. I discovered that his development empire built most of the original houses concentrated in the heart of the community and those that remain still provide regular people the chance to enjoy island living.

GOLDEN OPPORTUNITY

Born in Pensacola, Florida, in 1903, Long moved to Charleston at age 15 and went on to study at the University of South Carolina, where he played basketball, baseball and served as captain of the Gamecocks football team. He received a law degree in 1925, after bypassing undergrad studies, made juries cry as an attorney, and served as a state senator and on Charleston City Council. But he made his greatest mark as a driven real estate developer who erected apartment complexes and neighborhoods across South Carolina. “John Charles Long has moved through life powered by a dynamo of bountiful, turbulent energy harnessed by a shrewdness of character and ability which have spelled fortune and success,” assessed a 1951 Evening Post profile.

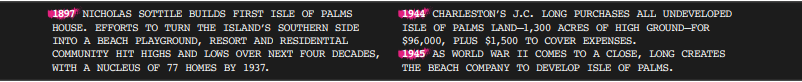

By several accounts, he found great satisfaction in the Isle of Palms, which he effectively took over in late 1944, when he bought all undeveloped property on the island, including 1,300 acres of high ground. During the early 1900s, Isle of Palms had been known for its famous Ferris wheel, pavilions and resort hotels, but the Depression, world wars and a series of fires stymied the developers who came before Long. His timing couldn’t have been better. At the end of World War II, the island emerged with gusto from wartime restrictions, military patrols and oil slicks from torpedoed tankers, a 1946 News and Courier article reported. Americans wanted to have fun again and a crowd of returning GIs needed places for their families to live.

TRANSFORMATION

Long launched The Beach Company to oversee the island’s development in coordination with other companies he created, such as The Worth Agency, which handled sales and rentals. By March 1946, the Evening Post proclaimed, “Mammoth Real Estate Program is Transforming Isle of Palms.” The push was on to sell both vacation homes and year-round residences on the island, which was easier to get to because of road upgrades, but still somewhat remote, with travel going through Sullivan’s Island.

THE TWO-BEDROOM COTTAGE

One of the quintessential J.C. Long styles is a simple, two-bedroom, pitched-roof cottage with about 800-square-feet of living space on a concrete slab foundation. Some of the earliest from the 1940s came with a Jack-and-Jill bedroom and shared bath. Later versions, like this one built in 1962, might have a carport, or a small porch on the back or side. While they are scattered around the island, look for clusters of these homes along Hartnett Boulevard, where this cottage can be found.

Long’s outfit preferred to do its own home construction. He filled in sections on the islands already developed southern side where he kept a summer house for his family and eventually built one on each side for his two daughters and started a corridor of new homes to the north, working inward from the ocean side along an extension of Palm Boulevard. Cleared lots provided native wood for many homes. Names of streets planned by an earlier developer Beach, Pine, Oak, Cedar and Holly became 21st, 22nd, 23rd, 24th and 25th avenues respectively, continuing the numbered system from the south. Long’s straightforwardness also showed in the no-frills houses that dominated most of his building and became his trademark; access to the Atlantic Ocean was always his biggest selling point.

SHAPING A COMMUNITY

“My father-in-law envisioned the Isle of Palms being for middle-class people,” Charles S. Way Jr., who married one of Long’s two daughters, says. “He never realized, never thought about it where you have million-dollar houses. That was just never in his vision.” Way, 78, talks with me for more than an hour at the headquarters for The Beach Company, which moved to downtown Charleston from Isle of Palms long ago and became the flagship for the family’s many businesses and development properties.

THE TWO-STORY DUPLEX

Isle of Palms duplexes often date back to the 1950s or earlier. There are several duplex styles, and some have been converted to single-family use, so they may not be as obvious. Look for two outside entrances, which might be side by side, at opposite ends or on separate floors with one reachable by outside stairs. Most duplexes were built within a block or two of the beach. You’ll find them running along and around Cameron Boulevard, starting at 22nd Avenue, and the island’s southern end has some left, too.

Now chairman of the board, Way started working for his father-in-law in 1962, after law school graduation. By then Long had turned the Isle of Palms into a bustling beach suburb with more than 1,200 year-round residents, and he was plunging into an expansion program that would introduce many brick ranch homes built by his LACO construction company. “If memory serves me correctly, you could buy a three-bedroom house with one bathroom for $11,750,” Way, who handled the furry of real estate contracts, says. The mortgage payment would be a little more than $60 a month, he recalls, “that was the sweet spot.”

Front porches were often forsaken because of the added expense. An economy of space caused features like small closets that would frustrate later generations. “Why waste room on a closet when you can put it in the bedroom?” Way explains. Long also “loved” low-cost concrete, and borrowing an idea from his brother, who built extensively in Puerto Rico, Long mass-produced a fat-roof, all concrete house on the island called the ALCON home. “At Last ... A Durable Beach Home Within the Reach of Everyone,” one advertisement proclaimed. Back then, an ALCON home would sell for around $5,000, Way estimates.

THE BRICK RANCH

Long and builder Henry Cone formed the LACO construction company, which built most, but not all, of the island’s single-story, 1960s brick ranch homes. The flat, rectangular LACO ranch homes typically had three bedrooms, with one or one and a half bathrooms. You can still find a lot of LACO homes in the heart of the island, on the cross streets that run between Waterway and Palm boulevards, like this one on 27th Avenue, and along the older Forest Trail streets. Some aren’t as obvious because owners placed siding over the uninsulated exterior walls. Several were elevated post-Hurricane Hugo.

Through the 1960s, development focused on finishing 21st to 41st Avenue and the Forest Trail neighborhood. Long didn’t bother building homes directly by the ocean, and there wasn’t a demand to live that close to the water. Way remembers his father-in-law had been happy to sell beachfront lots of for $2,500 each during the early days of the island’s development.

THE FLAT-ROOF CONCRETE HOUSE

Long tested out these shoebox-style concrete structures after being inspired by his brother, L.D. Long, who used a similar approach to large housing developments in Puerto Rico. Don’t be fooled by the stacked layers of concrete, which look like siding from a distance, and know that the tops of some flat-roof ALCON homes have been added onto. There are only a few easily identifiable ones left on Isle of Palms, mostly at the northern end of Cameron Boulevard, including this well-kept rental house. Others have not fared as well.

While Long continued to market Isle of Palms as a vacation place, he took extra measures to support the year-round community, providing land for several churches and The Exchange Club in $1-dollar agreements, helping create an idyllic place for many families.

EXCLUSIONS

But not everyone was welcome. In keeping with turn-of-the-century Isle of Palms practice, Long apparently restricted property from being sold or rented to anyone “not of the white or Caucasian race,” as evidenced by a 1947 listing of real estate covenants from The Beach Company that one Hartnett Avenue homeowner shared with me before I met with Way.

While black people could work on the island, they had to leave by 6 p.m., an expectation that continued at least into the 1960s, according to people who lived here during those days. Likewise, the beach was of limits to black people. The city archives contain a 1964 letter Long wrote to the mayor, asserting that the new Civil Rights Act did not apply to property The Beach Company owned between the ocean’s normal high-water mark and the main roads. He requested that “any negro citizen found walking across or trespassing on the property” be arrested and prosecuted.

The kitchen countertops in Sarah Stewart’s home are from the original J.C. Long construction.

When I ask Way about Isle of Palms beach segregation and the restrictive covenants, he responds, “All true.” But he says those were “different times” when much of everyday life in the Lowcountry was segregated. “Many, many subdivisions in Mount Pleasant, Charleston, West Ashley, North Charleston you would find that same covenant back then. But as I say, times have changed, a great deal.”

EVOLUTION

From early on, many full-time Isle of Palms families had military ties. City Councilman and Realtor Jimmy Carroll came here around the age of 5 in 1959 when his dad, a gunner on a destroyer ship, was assigned to the Navy base in North Charleston. His parents had heard about Isle of Palms from friends at the Great Lakes naval station. “This is the only home I know, and I watched it being built,” says Carroll, who takes me on a history tour that includes 30th Avenue, where Long once kept a construction yard.

The Bowden family and their English bull terriers use every inch of their 1964 LACO brick ranch.

Along the way, Carroll stops on 22nd Avenue to show me the duplex his parents first rented from The Worth Agency before moving to 37th Avenue. “What a cool spot to have grown up,” he says, remembering boyhood adventures, including a run-in with Long, who caught him climbing on construction equipment. “I got in so much trouble in this neighborhood, it’s unbelievable.” He stops and walks over to the white-sided home where he once lived. It was originally split into two apartments but has been converted into a single-family residence. Soon Gary Nestler sees us and pops outside to talk. He and his wife live there with their middle school daughter and are responsible for overhauling the 1949 building. He explains how they dressed up the outside, gutted the inside and added onto the back. “It’s got good bones in it,” says Nestler, adding that it’s a work in progress. “I think we can do a lot with it.”

USING EVERY INCH OF SPACE

Most homes built on the island’s interior streets from the mid-1940s to the early 1970s were J.C. Long homes of one kind or another, based on my interviews and past newspaper articles I came across. The block of 23rd Avenue where my husband and I currently live with our three children happens to be an exception, with older homes from other builders.

The kitchen countertops in Sarah Stewart’s home are from the original J.C. Long construction.

Some homes from that era have been lost to Hurricane Hugo in 1989, and others have been torn down and replaced by much larger, upscale residences that tower over the original homes that are left. That trend will likely continue due to rising insurance premiums and restrictions on improvements to buildings with ground-floor living space. But the J.C. Long homes that remain keep island living in reach for many people.

Our friend Janalyn Bowden, a real estate appraiser, briefly lived in a 3,500-square-foot home in West Ashley before downsizing with a move in the early 1990s to Isle of Palms, where she met her husband, Ray. “I wanted to be near the beach,” Bowden, who walks her two English bull terriers by the ocean most mornings, says. “It’s a different lifestyle than even Mount Pleasant.” She initially rented and considered some foreclosure homes outside the gates of Wild Dunes resort before she and Ray decided on a 1964 LACO brick ranch on 24th Avenue, because they liked the neighborhood feel.

Ray Bowden grew up four blocks away in a similar brick ranch on Waterway Boulevard during the 1970s, never wanted to leave the island and wound up working at Wild Dunes, where he’s now an engineering supervisor. Their son finished Sullivan’s Island Elementary School two years ago and played sports at the Isle of Palms rec center, just like his dad. They drive their golf cart to the marina to see friends at the end of the workday and keep their boat in front of the house ready for the weekends.

Previous owners expanded their house on the front and to the side. The Bowdens wound up doing more updates and renovations, including an addition with an extra bathroom in the back. They use “every inch” of the home’s 1,853 square feet, Janalyn says. She has appraised several other LACO brick ranches through her work, and the original floor plans are almost identical. “But then people take them and do different things with them.”

DETERMINED TO STAY

With property values on the island escalating once again, it might be tempting to sell out. But there are homeowners like Sarah Stewart, who lives less than a block from the ocean in a two bedroom, one-bath cottage on 32nd Avenue, who won’t consider it, despite the offers she receives. “I get letters,” she tells me with a smile as she looks out her window. “And here I sit.” Her father and an uncle bought the 1948 cottage together in the late 1960’s and decided to share it for family vacations. Stewart recalls arriving home from school on Fridays in Winnsboro to learn they were headed to the beach for the weekend. “It’s still one of the best memories of growing up.”

Her nursing career brought her to the Charleston area after she graduated from Clemson University in 1986, and she has lived in the house full-time ever since, frequently sharing it with visitors. “Even though it’s my house, it’s still the family beach house, and that’s the way it needs to be.” She had to repair a collapsed roof post Hugo, but has never expanded, and while she would like to add an extra bathroom, or even a washer and dryer, she manages with the space she has. Like many of the people we know here, she’s willing to make sacrifices to live on Isle of Palms. “This is home,” she says. “It just is.”